Sequencing Pseudomonas putida, Predicting Pyoverdine Structure

In my previous post I showed a bacteria isolated from the water around the roots of a Jade plant on our windowsill, which secreted something that fluoresced a lovely blue under UV light. My best guess was that it was some species of Pseudomonas, and the blue was from pyoverdine. But how can we know for sure? Well, I put it off because money, but since I like working with this bacteria and want to do more with it, I figured I’d bite the bullet and pay the ~$120 to get my answers :) It turns out that the closest match is P. putida, and that the pyoverdine variant that this makes is probably different to anything documented in the literature. Exciting stuff! Update: found a likely match in the literature - see end of post :)

I’ve also recorded a video (30/01) above for those who prefer that format.

Sequencing with Plasmidsaurus

I went with Plasmidsaurus’ ‘Standard Bacterial Genome Sequencing with Extraction’ service. I sent the sample (~15mg cells suspended in Zymo DNA Shield) off on Tuesday morning and by Wednesday evening the results were ready.

Species ID (Mash)

- Best match: Pseudomonas putida NBRC 14164

- Identity: 95.6% (1946/5000 shared hashes)

Genome Quality (CheckM)

- Completeness: 99.88% — excellent!

- Contamination: 2.15% — very low

- Lineage marker: Pseudomonas

Assembly Stats

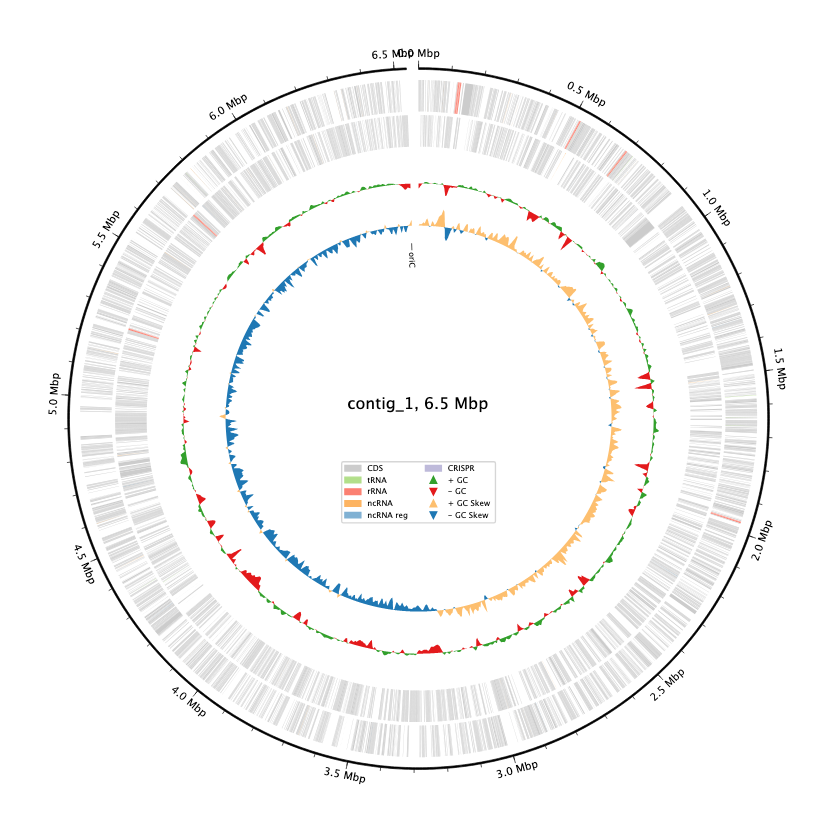

- Genome size: 6.54 Mb (typical for Pseudomonas)

- Total reads: 66,830 (398 Mb total)

- Estimated coverage: ~58x

- Longest read: 88.4 kb

- Read N50: 9.7 kb

They give you lots of data, including annotating the genome for you with bakta. Great stuff! We can see right away that our guess was right - this is a Pseudomonas species (P. putida is the closest match) and are ready to dig in further to see what we can learn.

Pyoverdine Investigation

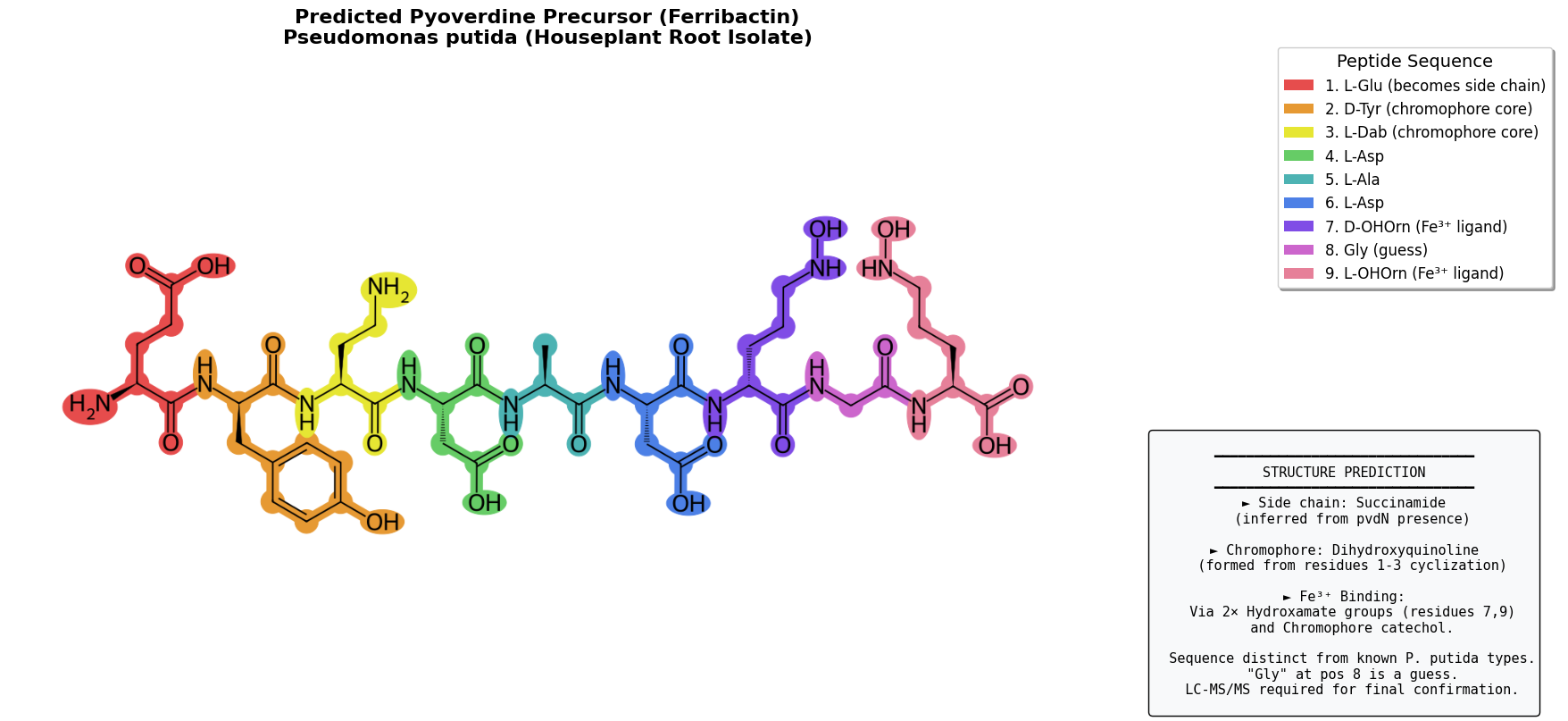

Pyoverdines vary but all come with three key parts: a dihydroxyquinoline core, a peptide chain, and a side chain. The peptide chain especially varies strain-to-strain - see here for some examples.

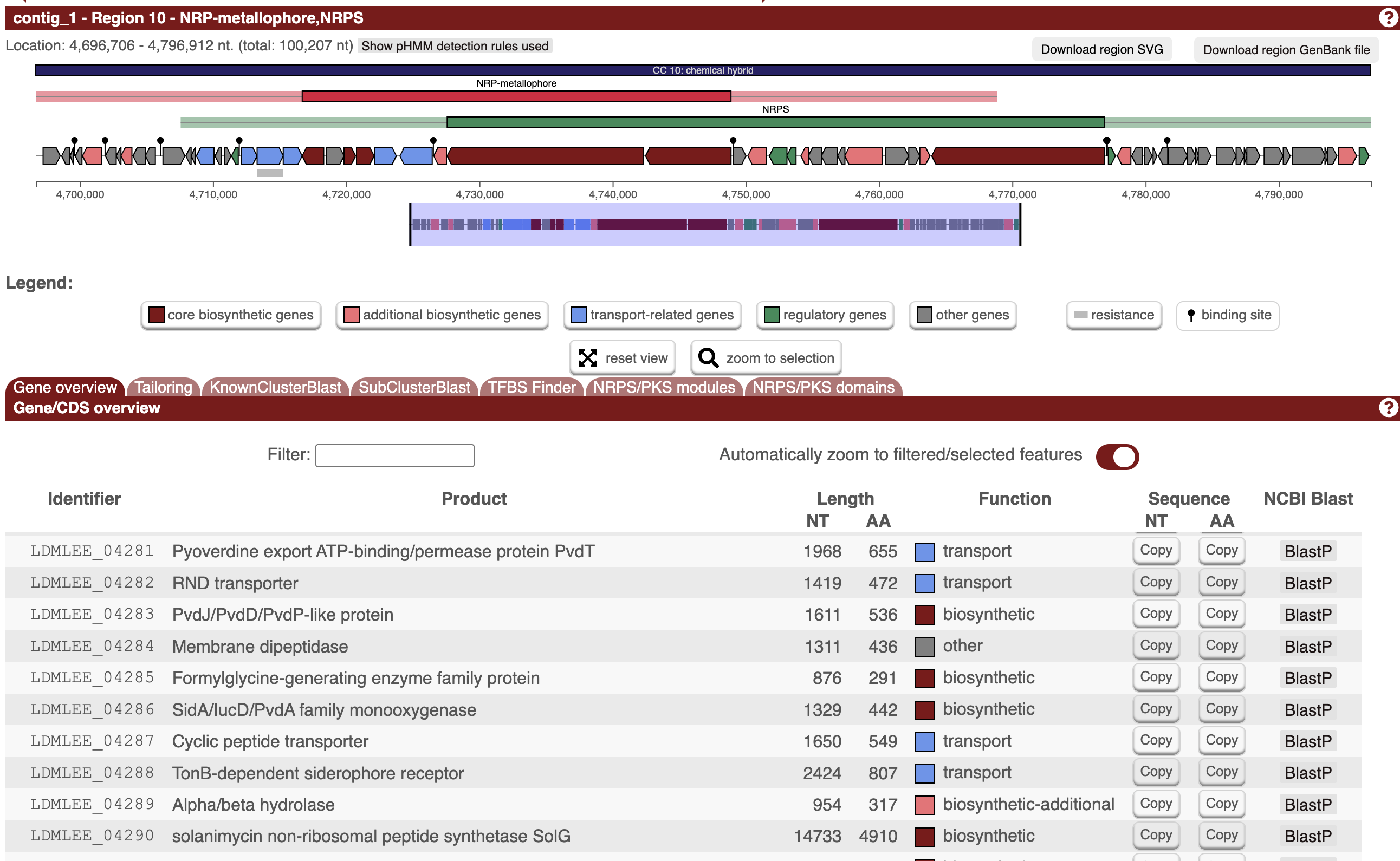

Step one was looking for the pyoverdine Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC). A Deep Research run gave some promising genes to start the hunt with. Some hits let us narrow in on a key region between 4.71 and 4.76M bp, with a number of promising-looking genes. A tool called antiSMASH likewise identified a region (4,696,705–4,796,912), labeled as ‘NRP-metallophore’ - this is our BGC alright :)

By looking at the A-domain predictions for this region, we can start on a predicted peptide sequence: Glu-D-Tyr-Dab─Asp─Ala─Asp─D-OHOrn─X─OHOrn (where Glu-D-Tyr-Dab forms the conserved pyoverdine chromophore after cyclization). That X is an unknown, which we’ll have to work on later - my best guess was Gly, although a later lit search makes me think Ser (see later update section).

The next step is to figure out which side chain is present. (Some strains make some of both). The side-chain type is determined by which gene is present:

- pvdN (PLP-dependent aminotransferase) → succinamide side chain

- ptaA (periplasmic transaminase) → α-ketoglutarate side chain

We BLAST the genome against known reference sequences, finding an 83% match to PvdN (NP_251095.1) but only a 23% match for PtaA (AAY94407.1) -> fair guess that this strain produces succinamide side chain.

This info gives us enough info to reasonably guess at the structure of the pyoverdine precursor (ferribactin):

Here’s a notebook running over the steps, with some light annotation. (I’ve since been fiddling a bit more, LMK if you’re wanting to dive into this deeply)

Future Plans

It’s one thing to poke at a genome and predict a structure, it’s another entirely to verify it. I’m hoping to work with a local university to run LC-MS on this to answer a few remaining questions and nail down the final structure exactly. Will require dusting off and improving my organic chemistry and learning a lot more! Stay tuned for that in some future blog post hopefully :)

Also, it’s probably obvious but worth stating explicityl: I AM OUT OF MY DEPTH HERE AND EVERYTHING IN THIS POST SHOULD BE TAKEN WITH A GRAIN OF SALT, ESPECIALLY WHILE IT IS MARKED ‘DRAFT’ :)

For the curious, raw data is on Google Drive, I’m open to questions @johnowhitaker. This solveit dialog has the key code in a nice rendered form.

Update: A Potential Match

In A combinatorial approach to the structure elucidation of a pyoverdine siderophore produced by a Pseudomonas putida isolate and the use of pyoverdine as a taxonomic marker for typing P. putida subspecies BioMetals, 2013 I found the following: P. putida BTP1/90-40 Asp–Ala–Asp–AOHOrn–Ser–cOHOrn (citing Jacques et al. (1995)). This is pretty much spot on for ours, and would mean the mystery X is Ser (serine), not Gly as guessed. It also answers a mystery - I’d been searching fruitlessly for pvdF in my genome to figure out if OHOrn gets formylated, this would indicate it doesn’t in this case.

AOHOrn = “amide-linked” hydroxyornithine (connected via α-amino group)

cOHOrn = “cyclic” hydroxyornithine (C-terminal, forms lactam ring with its own side chain)

BTP1/90-40 is the strain from the paper

fOHOrn/formyl-hydroxyornithine is the formylated form (hehe) of hydroxyornithine, pvdF is the “hydroxyornithine transformylase enzyme” that does this in some Pseudomonas.

PS: Molecule viewer test

Here’s the predicted ferrobactin precursor molecule, copied from the output of this code:

<canvas id="undefined" width="1000" height="750" style="width: 400px; height: 300px; padding: 0px; position: absolute; top: 0px; left: 0px; z-index: 0;"></canvas><canvas id="undefined" width="1000" height="750" style="width: 400px; height: 300px; padding: 0px; position: absolute; top: 0px; left: 0px; z-index: 0;"></canvas></div>