Language Models for Protein Sequence Classification

A 3D model of a protein kinase

We recently hosted a Zindi hackathon in partnership with Instadeep that challenged participants to predict the functional class of protein kinases (enzymes with some very specific functions in the cell) based on nothing but their amino acid sequences. This kind of sequence classification task has lots of potential applications - there is a lot of un-labelled data lying around on every computational biologist’s computer, and a tool that could guess a given protein’s function would be mighty handy.

Just one problem - it’s not exactly a simple task! There are 20-something amino acids which we represent as letters. Given a sequence like ‘AGASGSUFOFBEASASSSSSASBBBDGDBA’ (frantically monkey-types for emphasis) we need to find a way to a) encode this as something a model can make sense of and b) do the making-sense-of-ing! Fortunately, there’s another field where we need to go from a string of letters to something meaningful: Natural Language Processing. Since I’d just been watching the NLP lesson in the latest amazing fastai course I felt obliged to try out the techniques Jeremy was talking about on this sequence classification task.

The Basic Approach

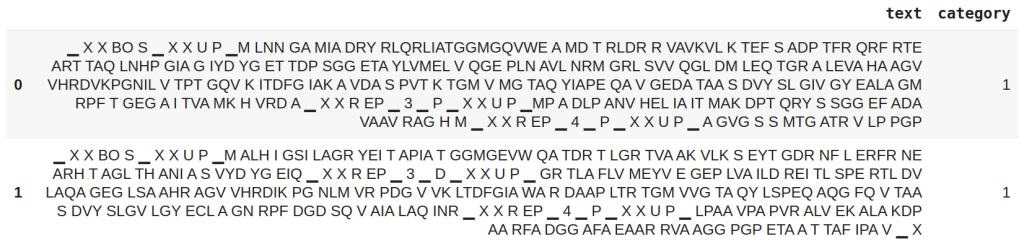

Tokenized input (left) and class (right)

Treating this as a language task and drawing inspiration from ULMFiT[1], this was my basic approach:

- I tokenized the sequences using ‘subword tokenization’ which captures not just individual amino acids as tokens but common groupings as well (eg ‘EELR’ is encoded as a single token). I think this basic approach was suggested by the SentencePiece paper[4] and it’s now part of fastai[5].

- I then created a ‘pretext task’ of sequence completion to train a ‘language model’ (based on the AWD-LSTM architecture[2]). The model learns to predict the next token in a sequence with ~32% accuracy - the hope is that in doing so it also learns useful embeddings and some sort of latent understanding of how these sequences are structured.

- We keep most of this network as the ‘encoder’ but modify the final layers for the actual task: sequence classification. Thanks to the pre-training, the model can very quickly learn the new task. I can get to 98% accuracy in a couple of minutes by training on only a small subset of the data.

- Training the model for the sequence classification task takes a while on the full competition dataset, but it eventually reaches 99.8% accuracy with a log_loss on the test set (as used in the competition) of 0.08, which is equivalent to 3rd place.

- Doing the normal tricks of ensembling, training a second model on reversed sequences etc quite easily bumps this up to glory territory, but that’s the boring bit.

It was fun to see how well this worked. You can find a more detailed write-up of the initial experiments on that competition dataset here. Spurred by these early results, I figured it was worth looking into this a little more deeply. What have others been doing on this task? Is this approach any good compared to the SOTA? Has anyone tried this particular flow on this kind of problem?

Getting Formal

It should come as no surprise that the idea of treating sequence classification like a language modelling task has already occurred to some people. For example, USDMProt[7] turns out to have very nearly the same approach as that outlines above (self-five!). Their github is a great resource.

There are other approaches as well - for example, ProtCNN[6] and DEEPPred[8] propose their own deep learning architectures to solve these kinds of tasks. And there are some older approaches such as BLAST and it’s derivatives[9] that have long been standards in this field which still do decently (although they seem to be getting out-performed by these newer techniques).

So, we’re not the first to try this. However, I couldn’t find any papers using anything like the ‘subword’ tokenization. They either use individual amino acids as tokens, or in rare cases some choice of n-grams (for example, triplets of amino acids). The advantage of subword tokenization over these is that it can scale between the complexity of single-acid encodings and massive n-gram approaches by simply adjusting the vocabulary size.

Your Homework

I did some initial tests - this definitely smells promising, but there is a lot of work to do for this to be useful to anyone, and I don’t currently have the time or compute to give it a proper go. If you’re looking for a fun NLP challenge with the potential to turn into some interesting research, this could be the job for you! Here’s my suggestions:

- Pick one or more benchmarks. Classification of the PFam dataset is a nice one to start with. The ProtCNN paper[6] (quick link) has done a bunch of the ‘standard’ algorithms and shared their split as a kaggle dataset, so you can quickly compare to those results.

- Get some data for language model training. The SWISSProt dataset is a nice one, and for early tests even just the PFam dataset is enough to try things out.

- Train some language models. Do single-acid tokenization as a baseline and then try subword tokenization with a few different vocab sizes to compare.

- See which models do best on the downstream classification task. Lots of experimenting to be done on sequence length, training regime and so on.

- For bonus points, throw a transformer model or two at this kind of problem. I bet they’d be great, especially if pre-trained on a nice big dataset.

- If (as I suspect) one of these does very well, document your findings, try everything again in case it was luck and publish it as a blog or, if you’re a masochist, a paper.

- … profit?

I really hope someone reading this has the motivation to give this a go. If nothing else it’s a great learning project for language modelling and diving into a new domain. Please let me know if you’re interested - I’d love to chat, share ideas and send you the things I have tried. Good luck :)

References

[1] - Howard, J. and Ruder, S., 2018. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.06146.

[2] - Merity, S., Keskar, N.S. and Socher, R., 2017. Regularizing and optimizing LSTM language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.02182.

[3] - Smith, L.N., 2017, March. Cyclical learning rates for training neural networks. In 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) (pp. 464-472). IEEE.

[4] - Kudo, T. and Richardson, J., 2018. Sentencepiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.06226.

[5] - Howard, J. and Gugger, S., 2020. Fastai: A layered API for deep learning. Information, 11(2), p.108.

[6] - Bileschi, M.L., Belanger, D., Bryant, D.H., Sanderson, T., Carter, B., Sculley, D., DePristo, M.A. and Colwell, L.J., 2019. Using deep learning to annotate the protein universe. bioRxiv, p.626507. (ProtCNN)

[7] - Strodthoff, N., Wagner, P., Wenzel, M. and Samek, W., 2020. UDSMProt: universal deep sequence models for protein classification. Bioinformatics, 36(8), pp.2401-2409. (USDMProt)

[8] - Rifaioglu, A.S., Doğan, T., Martin, M.J., Cetin-Atalay, R. and Atalay, V., 2019. DEEPred: automated protein function prediction with multi-task feed-forward deep neural networks. Scientific reports, 9(1), pp.1-16. (DEEPPred)

[9] - Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schäffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W. and Lipman, D.J., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids research, 25(17), pp.3389-3402.